Working Womenʼs History Project

Connecting Today with Yesterday

Making Women's History Come Alive

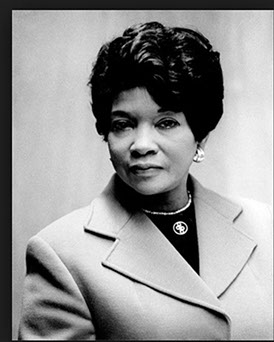

Rev. Addie L. Wyatt

The Reverend Addie L. Wyatt, 1924-2013.

Wyatt at the Amalgamated Meat Cutters headquarters in 1977, where she served as the union's international vice president.

Women packing bacon, 1950s.

Wyatt with fellow union officials at a NAACP conference, 1950s.

Wyatt (second from right) marches in support of the Equal Rights Amendment in Chicago in 1980. Also shown are TV celebrities (left to right) Phil Donahue and Marlo Thomas, feminist author Betty Friedan and actress Jean Stapleton (far right).

Photos credit: American Postal Workers Union AFL-CIO

nterview by Joan McGann Morris

Transcribed by Helen Ramirez-Odell

Rev. Addie Wyatt: “Racism and sexism were economic issues.”

It is December 14, 2002. I am very honored to be in the home of Rev. Addie L. Wyatt, who is the Co-Pastor Emeritus of the Vernon Park Church of God in Chicago, Illinois, along with her husband, Rev. Dr. Claude S. Wyatt, Jr. who has worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from 1958 to 1968 and has participated in major marches in Selma, Alabama, Washington, D.C., and Chicago. She spent thirty years as a leader and officer of the labor movement, retiring in 1984 as Vice President of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union. In 1975, Addie Wyatt appeared on the cover of Time magazine as one of its Women of the Year.

She is currently the CEO of the Wyatt Family Community Center which is a couple of blocks from her home. I am interviewing Rev. Wyatt in conjunction with an award she will be receiving in March 2003 at the Gala for the Working Women’s History Project at Roosevelt University. I am with my husband, Ken Morris, who is a composer and our audio-visual coordinator, and Sue Straus, who is the president of the Working Women’s History Project. We are very honored to give Rev. Wyatt the Mother Jones Award from our organization. We want to her to talk about history and how her own life has mirrored the history of not only African-American women in Chicago, but also the leaders of Chicago who are mothers and grandmothers and the working women who have been involved in unions.

Morris: As I understand, Rev. Wyatt, your family moved to Chicago along with many other Blacks during the Great Migration in the early part of the century. When did your family move to Chicago?

Wyatt: In the year 1930

Morris: How old were you at that time?

Wyatt: Six

Morris: Can you tell us a little bit of how it was to be in Chicago at that time?

Wyatt: First I must say how it was to leave Mississippi. That was the only place that I knew and that was in Brookhaven, Mississippi. I did not want to leave Brookhaven. But I was told that we were going to a place where we would be so much better off. I thought it meant the land of the free. But when we came to Chicago, I was shocked that we did not have fruit trees in the yard. We did not have vegetables. We did not have cattle or chickens, and all of this we had in Brookhaven, Mississippi.

During the years that we were struggling for survival as a family, we almost starved because it was so difficult getting work and providing for your families. So I had mixed emotions about coming to Chicago. I thought we should have stayed in Mississippi. Of course, I’ve changed my mind now.

Morris: What did your parents do?

Wyatt: My mother in Mississippi was a teacher and, of course, she could not teach here. She was an excellent seamstress. My father was a tailor and when he came to Chicago he couldn’t work here as a tailor. My mother could not find work as a domestic worker. She could not find work here as a teacher because she did not have a degree. In the south it was different. If you had a high school education, as you know, you could teach.

Morris: How many people were in your family?

Wyatt: At that time there were five children, my mother, my father and my paternal grandmother.

Morris: And where did you come in the family?

Wyatt: I’m number two. I had an older brother. I’m the oldest daughter and number two in a line of eight.

Morris: That’s a big family.

Wyatt: That’s a wonderful big family.

Morris: Had your family always lived in this area the south side of Chicago?

Wyatt: No. For a short time we lived on the west side of Chicago. Of course, when we first moved here to Chicago we lived on the south side and most of our life has been on the south side. When we married, my husband and I lived in Altgeld Gardens, which was a housing project at 130th Street and Evans in Chicago.

Morris: So when you said that your father had a hard time getting a job as a tailor and your mother had a hard time getting a job as a teacher, what did they end up doing?

Wyatt: Well, we ended up on what they called at that time charity, which is like relief now. And depending upon family members to also supplement.

Morris: I know from your background that you are highly motivated and highly educated. Was this instilled in you by your parents? Where does this come from in you?

Wyatt: By my parents and by my church. We were very active in our church and that was what helped us to make it through the very difficult times our faith in God and our faith in our family and in our neighbors.

Morris: Were your parents also very active in the church?

Wyatt: My mother and my grandmother were. My father later on before he passed became active in the church.

Morris: Eventually you ended up getting work in the labor movement. But I understand that initially you went for a job as a secretary?

Wyatt: Yes. I went to work at Armour and Company in the city of Chicago. You know, when I was a child, I detested being poor and not having enough to eat and a decent place to stay. I always thought that something could be done to make life better for us. I would raise that question with my mother from the time that I was four or five years old. She would say to me, “Life can be better, Addie, but you will have to help make it so.” I didn’t altogether know what she meant, but it stayed in my mind that there was something that I had to do to make life better for myself and for my family. Therefore, I went to work at an early age because I knew that change had to come if we were going to survive.

I went to work at Armour and Company. When I went there I was out of high school and I could type 60 or 70 words a minute. I thought I could get a job typing. But when I went to Armour and Company I applied for a butcher’s job. Of course, when the man came out to test the butchers by the sharpening of your knives, he could tell right away that I wasn’t a butcher. But I looked over at the other side of the room and there were six young white women waiting for something and I thought I’d wait with them. In a little bit, an attractive young woman came out and called for typists. I thought, oh God, that’s me. And I went with the six young white women and I applied for the typing job. I passed. And they hired me. But when I told people and friends that I got hired at Armour and Company as a typist, I later learned why they snickered and why they laughed. Because they knew what I didn’t know that they did not hire black typists.

When I reported to work Monday morning, they sent me straight to a canning department packing stew in a can for the army, because that was in the year 1941 and we had just entered into World War II. I was so disappointed and I began to inquire among the others there about the job and say to them that I was just there temporarily because I’m going to work in the office as a typist. They just snickered because they knew what I didn’t know at that time. But as I worked there and began to inquire about salary, I was told that the salary was 62 cents an hour for women. Of course, at that time if you were a typist you might have earned something like $19 a week. If you were black and light–complexioned, you might have earned something like $12 a week. And if you were black like me and got hired at all, you might have earned something like $8 a week. Of course, $24 a week was more money than I had ever seen in my life and I decided to stay there on the line packing stew in a can.

Morris: How was that? Was it hard to learn to do that?

Wyatt: No, it wasn’t hard to learn. It was fast work. You were in motion the whole eight hours. You were constantly moving, taking cans off a conveyor to weigh the cans for accurate weight and putting the cans back on the line. You had to do that for eight hours.

Morris: Was that without a break?

Wyatt: No, at that time the workers had a union and of course, I didn’t know what the union meant. They had a coffee break which I could never take because I had a small child. Whenever I had a break I would call to see about the child. By the time I was through getting a turn on the telephone, it was time to get back to the line as the whistle was blowing and the machines were starting. This was in 1941 and I was 17 years old.

Morris: You’ve had to wear many hats as a wife, mother and a worker. How did you manage that over the years?

Wyatt: Well, thank God I was well trained by a loving mother and a grandmother. As an older sister, you had to help take care of the other children and do the housework. From the age of eight, I helped to cook to prepare for the children. So a lot of skills I learned by precept and example in my home. My church provided me with spiritual depth and understanding how to live with other people, how to live with myself most important, and so when I went to the job at that early age I was able to do the job, but also I was able to do the job at home.

Morris: Did you have a sense of the racism that existed? How did that affect you when you weren’t able to get the initial job you went for because you were African-American?

Wyatt: It really didn’t strike me at first. When we were small in the South, I knew that Blacks were discriminated against. At that time we were called “colored” and colored people were discriminated against. It wasn’t until I started in the paid workforce of this nation that I discovered that women were also discriminated against. Facing the discrimination as a race and as a woman, something woke up within me. I remember my mother said life can be better – you have to help make it so. I would raise the question in my mind What can I do? I have got to do something. I can’t tolerate, I can’t deal with racism and sexism.

I discovered that this was one of the reasons why we were poor. Racism and sexism was an economic issue. It was very profitable to discriminate against women and against people of color. I began to understand that change could come but you could not do it alone. You had to unite with others. That was one of the reasons I became a part of the union. It was a sort of family that would help in the struggle.

Morris: When did you meet your husband during this time?

Wyatt: I met my husband when I was in high school. I was a sophomore in high school when I was 14 years old. I went to high school at the age of 12 and most people thought I was older. I guess it was because of my maturity from child up. He was a senior and I thought he was the most handsome man I had ever seen. He was such a wonderful young man. My mother loved him. My family loved him and I do too.

Morris: What were the circumstances? How did you meet?

Wyatt: I was in the high school band and I played the first clarinet in the concert band. My husband was attending classes that I had and his period of class was always an hour or so before mine. We would meet in the hall and I wanted to be sure that he passed the test and that he knew what was happening in class that day and I would talk with him and he would talk with me.

Morris: Was it instant attraction on both of your parts?

Wyatt: I knew it was on mine.

Morris: When did you get married?

Wyatt: We got married in 1940. We’ve been married 62 years and never been apart. I’ve been married to the same handsome, wonderful man who helped me to not only raise our children, but helped me to raise my mother’s five children that she had when she died at the age of 39.

Morris: So, in your family you have five children of your mother’s and two sons and a number of grandchildren?

Wyatt: Yes. We have eight grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

Morris: What did your husband do early in your marriage in terms of work?

Wyatt: Right after my mother died in 1944 he was drafted into the navy so I was left alone with seven. Before then he worked in a cleaners. After that time, he worked in the post office as a finance clerk.

Morris: Was he also involved in unions at that time?

Wyatt: Yes, he was. He was not actively involved but he was a member of the union. He started working at Armour and Company before I did, but only for a short time.

Morris: How did he take to your involvement with the unions and with the civil rights movement?

Wyatt: He was also involved in the civil rights movement. It was in 1956 that we met Dr. King and our union was the first union to invite him to the city of Chicago. My husband worked with the civil rights movement too. He worked in the union with us and was involved all along.

Morris: What were the circumstances of your meeting Dr. King?

Wyatt: Our union was the first union to invite him to the city of Chicago. At that time I was a program coordinator for District One of the United Packinghouse Workers Union. The late Congressman Hayes (Charles Hayes) was my director. He had made commitments to Dr. King and the movement to raise money for the Montgomery Improvement Association. And of course, as a coordinator, he gave me the assignment to do the work. So I had to cover five states to raise funds so that we would have our quota. Thank God, we did very well because, number one, I had faith in God, faith in the movement, and faith in the people, white and black, that we were serving. We raised the largest amount of any district in our union. When Dr. King came, we had to present this money to him for the Montgomery Improvement Association.

Morris: We have never had the privilege of meeting Dr. King directly. Is there anything in particular you remember about Dr. King that you would like to convey to us?

Wyatt: He was a sincere person with great faith in God and great faith in people. He loved people. He had a great sense of humor. There were times when we’d meet together it was so wonderful to see him relax and laugh heartily at things that would happen some experiences that we go through, and he and I would pray from time to time as I do with most of our leaders, knowing what they go through and praying for their families. Knowing Dr. King’s great love for his wife, Coretta, and his children, I would always take the opportunity to steal away and pray with him to keep him

encouraged. He was faithful, true to his commitment. There were times when we would invite him to come to speak for us, and he always would compliment me by saying, “Addie, I’m coming because you called me, and I know you wouldn’t be calling me for just anything. You know how busy I am.” And that was so true. He was a very wonderful person and a person that you could love. He was a great eater. He loved to eat and we would do that so often as we would share with each other.

Morris: What did you and your husband like to eat and what did Dr. King like to eat?

Wyatt: Well, it’s always chicken and barbecue. I can recall on one occasion when we were meeting at Rev. Willie Barrow’s home, he was coming in and he came in late, and when he got there to her home he just laughed at Rev. Barrow. He said, “Girl, Why do you have all this china and this silverware polished? All we need is our fingers to eat this barbecue and this chicken. He would dine with us and we would laugh and talk, and then he would teach us. We learned many things from him how to relate to the opposition, how to love not because of, but in spite of .”

Morris: When you were working with Dr. King, at times did you sense that there was danger? What kept you going?

Wyatt: Faith in God, and faith in the people that we were working with, and faith in Dr. King’s commitment and what the struggle was all about. We knew we had to make change and that change was not going to come easy. Some of us would live and some of us would die, as some did. We went to Selma with him. I went down with Rev. Barrow and six white women from the Chicago area. There were fearful moments there. Just before we arrived in Montgomery, you could look out and see the Klan on horses with their uniforms on.[full regalia with hoods covering their faces] We were told that some of them had come to pick us up.

When we were called to Selma, they told us not to leave with anyone because they had not sent anyone to pick us up. We stayed all night in the bus station, and slept there until the next morning when someone officially came to get us. We went into Selma and we were meeting at two churches. We’d have to come down the streets from one or the other. We marched to the County Building and we were abused and all kinds of things were said, but we were marching behind our leader who was Dr. King, and Dr. Abernathy, and some of the others. As long as you could see the leader still stepping, you felt like stepping along with them because you were there to give them support and help. The last evening that I was there, they incarcerated us, put us in jail, and I was to come back to Chicago to get my husband to get some of the other ministers so they could see what was happening. So I came back. One of the sort of fearful things was to come down that highway when Viola Liuzza was killed and I had to drive down there with the driver alone. Of course, I prayed all the way and I made it and got back home. I went to church on that Sunday.

We called a group of our ministers of the Church of God and a few others together and we inspired them and encouraged them to organize some other forces to go down to join Dr. King. So my husband left in a couple of days with 25 members to go down and join Dr. King. This he did and I went on back to the labor movement to my job I was working then for the movement – and to encourage others to prepare to send forces down to help. My husband met Dr. King and the others on the route to Montgomery. They joined them. It was several days before I saw them again and learned of their experiences as they marched and as they slept in the bus and whatever happened to them on their way to Montgomery.

Morris: We talked of your meeting with Dr. King and how you worked in Selma with him and how dangerous it was. You said that one of the white women, Viola Liuzzo who had been killed you had to drive down the same road from Selma to Montgomery. Did your group take any special precautions for your safety?

Wyatt: Yes. There were instructions given to each of us as you entered Selma. We had meetings where Whites were told how they had to protect the Blacks when you were attacked. White women were told that if you were marching with a black man, and he was attacked, you had to fall upon him to protect him, and a white man would fall upon the black woman to protect her. We marched, black and white, together. I can recall one day at church in the meeting, I went downstairs to the washroom and all of a sudden I heard rumbling going on upstairs. Rev. Barrow ran downstairs to try to get me. She said, “Everybody’s gone and you’re left here so you better come on because I’m leaving you too.” And I was trying to get up to get out of the washroom and I came out just as I was, trying to make it down the street with her. There was shooting and everybody was getting back to the larger church. When we got back down there, we were incarcerated. We had to stay in the church and some had to stay in the jail.

Morris: Did they charge you with anything or did they just put you in jail?

Wyatt: They just put us in. They didn’t charge us with anything.

Morris: Who were you with at the time?

Wyatt: I was with Rev. Barrow, and of course, Dr. King was there with us. There were some who were incarcerated in the physical jail. We called to tell their relatives and their parents because the news would carry the information and it would be frustrating and frightening for some of the families. We were trying to get others to come down to join the team.

Morris: How long were you in jail and did they give you any reason when they let you out?

Wyatt: No. We were in all day and all night. We were talked to by Dr. King and some of the others who would encourage and inspire us and tell us what we had to do.

Morris: Can you remember anything that was said to you by Dr. King at this time?

Wyatt: They were telling us over and over again, pray. Don’t retaliate, and if you could not take the abuse, it would be best to go. You may go back rather than stay there and become a real problem. That was a learning experience for some because some did go back. Some of them would not tolerate being sick or spit on, and this is what would happen.

Morris: What did they say to you when they let you out?

Wyatt: They just tell you how to conduct yourself, and of course, there was constant praying and singing which was encouraging, and you were stimulated by the support and unity of the group.

Morris: Did you and your husband have any fears about being involved since you were parents? How did you deal with that with your children?

Wyatt: We talked to our children about what it was that we were doing. We had the responsibility of trying to help make the world better for them, and it was for them that we were involved in the struggle. “If the world was going to be better, we had to make it so.” These are the words of my mother, which I never forgot.

Morris: Later on you were one of the founders of NOW, the National Organization for Women and you were also one of the founders of CLUW, the Coalition of Labor Union Women. This was in addition to your other jobs, including being a mother and a Reverend. Could you give us the sequence of that?

Wyatt: The reason we were involved with NOW was because the women were in the struggle to improve their lives. To give the help that each other needed, we had to change a lot of things. We were members of the Commission on the Status of Women. If you can recall, the late Eleanor Roosevelt appointed us to serve on the Commission. The job that was given to us was to make a study of American women to find out what the problem was – what was really happening to them what they desired what they wanted what was needed to change the status of women. As we made that

study, we traveled from state to state and held meetings where women from all walks of life came together to talk about the status of women in America. There were some of us who would relate to each other whenever there were special meetings called. Some of them were members of the organized labor movement. Some were members of the religious movement, political movement, various movements.

Some of our sisters who founded NOW had a feeling that this wonderful report of American women would just be shelved and nothing would be done about it. And so they were organizing so we could be reasonably sure that change would come and that the record would not be hidden. The story would be told, and together, we would do something to change the status of American women. That’s why we organized NOW.

Morris: What year was that when you founded NOW along with the other women?

Wyatt: That was about in 1963 if I can remember.[talks started in 1963, NOW was founded officially in l966}.

Morris: And so, it was President John Kennedy who asked Mrs. Roosevelt to call this Commission on the Status of American Women? Do you recall what struck you from that report? What was important for us to know about that report that you don't want us to forget?

Wyatt: That contrary to the thinking of so many, women were not satisfied with their status. And if they were, they could not be because we had to shake them up - to let them know that we had a role to play in improving the lives of God's human beings who happened to have been born female.

Morris: Your husband has been supportive all along of your work. What were his feelings when he found that you were such a leader in the women's movement?

Wyatt: By that time he was also a leader. Because I had been a leader in the organized labor movement, but our women's movement started in the organized labor movement. Because one of our greatest themes was to make life better for women. Especially after I first found out, when I was working at Armour and Company, that men made 14 cents an hour more than women working on the same line. I've always been a person from a child up to raise questions, why. And I raised that question, "Why?" And they told me it was because women didn't deserve to earn as much as men, and that women did not work as hard as men and they did not have to do heavy work like mine. Any more of that turned me on. It really turned me on. Because I guess one of the reasons it turned me on was because so many women felt that way too not just me.

We had to educate ourselves. We had to stir them up and we had to talk to our women about why we were really discriminated against. It has nothing to do with who has to do the more difficult jobs. It was because we were female and it was profitable to discriminate against somebody, and the somebodies that were discriminated against were those who were of color and those who were female; also, those who lived in geographical locations that were in the South. We had to make a change.

Morris: When we talk about status, you're talking about the economic conditions as well as the way people are treated?

Wyatt: The economic and political decision, the spiritual..

Morris: I want to go back to your experiences with the Armour Corporation and the Meatcutters. Were there workers who were reluctant to join the union? Did you have to persuade them to join the union?

Wyatt: The first union that I was in was the United Packinghouse Workers Union. Later on we merged with the Amalgamated Meatcutters. Later, we merged with the retail clerks, forming the United Food and Commercial Workers Union.

Morris: When you first got into the union, did you find that some of your fellow workers and the other women were reluctant to join?

Wyatt: That's true. I was reluctant too, because I didn't know what that thing was that they called a union. I just knew that at the time of need, some of those needs were supplied by the union. I had a grievance on the job. I was placed on a job of putting pins on the top the tops on the cans, rather, which I liked much better than packing stew in cans. The foreman said I did it very well. But in a few days they moved me off the job and they put a young white woman on the job who was just hired. And as I told you, when I don't like something, I always raise the question, 'why?' A young black woman on another line in that department saw me into it with the foreman. She came to find out what my problem was and I told her. She served the grievance and we went to meet with the superintendent of the plant two young black women sitting across the table from two white men who were the leaders there in the plant. Now, that was impressive to me. But I didn't think they could do anything and she raised my grievance, and after a while I talked and said what happened and what I thought. She pulled my frock for me to be quiet and I couldn't understand because I was ready to go. She took me outside and said to me, "Listen, whenever you win a grievance, don't keep arguing." I said, 'Did we win?' She said, "Yes, you're going back on the job, putting new lids on the cans." That was impressive to me. So I wanted to know about what made us win and all the things that go with it, and I found out that it was because of the union.

Morris: And you had some seniority on the job?

Wyatt: That's right.

Morris: Do you remember the name of the woman?

Wyatt: No, I never knew her name at the beginning and I didn't know it afterwards because I didn't see her anymore.

Morris: How old were you at the time?

Wyatt: I guess I must have been about 18.

Morris: So this was your first big involvement. When you decided to go from union member to union leader, how did that come about?

Wyatt: I had been in the union for a while. I had left Armour and Company and I was working at Illinois Meat Company. I had gone to a conference, called an anti-discrimination conference, which would be like a civil rights conference now. The union sent me as a delegate. When I walked into the room and I saw white workers, black workers, Hispanic workers, women and men, and when I heard the discussion that went on, how they were championing the cause of all these groups, and how they were talking about unity and togetherness, I knew then that this was the wonderful force this was the force that we need to have to bring about the change that I was looking forward to. They also inspired us and encouraged us to fight for male and female, black, white, Hispanic leadership. I knew this was important even though I did not want to be a leader in the union. I went back to my local union, made my report, and I organized with the other women and men to be sure that when we had the election, we had a woman and a man to serve in the leadership of the union. And they brought their ideas. But, the nearer we got to election day, we couldn't get anybody who would run for a woman vice president. So some of the elderly women came to me and said, "Honey, you're the only one who could really do this for us, and if you will, we will do everything we can to support you." And I said no, I could not do it, because I was already active in my church, in the community working with the young people, and I just could not take on this responsibility. But they talked me into it. In order to call their bluff, I agreed that I would run, but I never meant to vote that day. I never went to vote. I went straight home. When I came back the next day, they met me in the hall, congratulating me. I said, for what? "You're the vice president of our local union." I said, no. "Yes, you are. You won!" And then I didn't know how to tell my husband. It took me some time to tell him. Every time I would sit down at the table, it was so peaceful and nice I didn't want to raise that question. Finally, one day when I had to go to the meeting, I blurted out, 'Honey, I've been elected the vice president of my local union.' He said, "What! How are you going to do that with all that you have to do?" I said, 'I can do it because we've got to do it. We've got to make a change!' I talked and I talked. And he said, "Alright, if that's what you want to do. You can't let things go undone here." I said, 'Don't worry about that.' And so, that way I got the support from him. But the worst thing was my first grievance that I went to. I found out that the president, who was a young white male, a very wonderful person, had resigned. He had a personal problem and he could not keep the job. And so they said to me, "You'll have to take the president." 'No, I can't do that. I can't do it.' But I did it, and became the first woman president of a UPWA local union.

Morris: And so, the leadership was foisted upon you. When you think about leadership, what would you want young women nowadays what do you admire in a leader? Has it changed or is it the same? You are still a great leader within the community and in Chicago, and in the labor movement, and certainly in the church. What are the qualities that you admire and that you had to be able to accomplish this?

Wyatt: One has to have a commitment, integrity, and compassion for people and a willingness to work for them, to give to them and to receive from them, because it's always a give and a take. You're not giving all, without receiving much more than you give. My life has been tremendously blessed because of what I've been able to give and to receive in return.

Morris: You have been one of the founders of CLUW, the Coalition of Labor Union Women. When you were a founder of NOW, the National Organization for Women, what year was that?

Wyatt: That was about 1963, I think.

Morris: CLUW came along in 1974. What were the circumstances and the need that was met by CLUW?

Wyatt: We were working in coalition with many women, the religious women, political women, women in the civil rights movement, but there was no presence of organized women to be able to say that here we are and women here will speak for working women in conjunction with the women who are speaking for the religious community, the political community, and what have you. We decided that something had to be done. Not only that, we did not have women at the table in the labor movement speaking for women on the economic issues. We had to get them there, to train them and to be sure that they were inspired and willing to be a part of the struggle for better jobs and working conditions. That was the reason why we were called together, and seven women met at the airport here in Chicago, and we decided to pull the names of the women that we had we didn't have that many, and call them into a conference meeting, and this we did.

I guess we had maybe about 99 names to send an invitation to. Surprisingly so, when we had that first conference calling to see if women would be interested in organizing a committee or organization like CLUW, more than 200 women came. Some were just insulted because they didn't get invitations, and we had to try to explain that they didn't get invitations because we didn't have their addresses and didn't know where to find them. That was the beginning of CLUW. Women showed an interest and finally, in 1974, I had served as the coordinator of the committee. We didn't have any money, and we wouldn't dare go to ask our union leaders to give us money to organize a women's group called CLUW. I had $10 and went down to various places, and no place wanted to take us. They thought we were crazy. Then, I went down to the Pick-Congress and several of the women went together with me. Mrs. Abercrombie was a coordinator of their conferences and I told her our plight and said, 'I only have $10, but we expect to have about 1500 women and you won't lose a thing. If you give us this opportunity, you will be a part of the greatest history that this city has ever known, and this hotel will be grateful.' She looked at me and she said, "You can't get any money from Pat from your [union ] leadership?”

We said, “We probably could but we don’t want to.” And she let us have the hotel. We pinned down all of the rooms in the hotel. We pinned down cups of coffee for 1500 women, and also, we got her to give us lunch for 1500 people two lunches for 1500 people. We had $10 to make the deposit. The other thing is that the women were sending their registrations into my office. Thank God for Mr. Hayes, who was supportive of our struggle. He let me do the work in the office there. The women sent personal checks. You didn’t know whether they had a dime in the bank, but we banked the personal checks. The day came for that conference. We were expecting 1500 women, and I’m upstairs dealing with one of our women of the community who came from the welfare workers and wanted a welfare conference.

She gave us such a hard time, but I did get her to give us a chance to get union women organized and we’d be there for them. When I came downstairs, the workers were running to me: “We’ve run out of chips. We’ve run out of sweet rolls.” I said, ‘Take the sweet rolls and divide them in half. Divide them into quarters. Remember the loaves of bread and the fish? Then do that, and share with your sisters. The greatest thing that happened is that instead of 1500 people we now have over 3000.’ And when they were calling for me to come up and open the conference, I didn’t know where we were going, except I remember saying, ‘Oh, God, be with us now because we cannot fail.’

Morris: When this happened for CLUW, you really had a sense of where you were going at that time. We’ve already talked a little about your involvement in the civil rights movement with Dr. King, and your early years in Chicago, and how you became a union member and eventually a union leader, and got involved with the National Organization for Women and was one of the founders, and also of CLUW, the Coalition of Labor Union Women.

Morris: I wanted to touch a little more on your spiritual life. What made you become a Reverend and what year was it that you took that step?

Wyatt: My spiritual life was the most important part of my life. It has helped me to live in every other area. If I have been effective in these different areas, it is because of what God means in my life, and the commitment that I have made to God to love people, to work for them, and to make life better for all of them. This has been, really, the most important part of my life. I am ever grateful to my mother and my grandmother, most importantly, for instilling this faith within me, and for training me and for keeping me going to my church which is the Church of God. We can go back to that question because it has a certain feeling for me.

I got started in the church when I was very young. I played the piano for the church at the age of eight. At 12 years old, I was musician for one of our choirs. I have trained choirs and young people to sing and to share their faith through singing. Almost all of my life, I have been able to bring young people to Christ, and to help them to overcome

some of the difficulties that they have. Because of the work that my husband and I were doing in Altgeld with over 100 young people who were members of the Wyatt Corps Ensemble helping them to do things that were meaningful we then were encouraged to go into the ministry. Both of us did and both of us are ordained ministers.

Today, we have young people all over this country whose lives have been changed because of the ministry that we had. They are instrumental in helping other young people. Some of them were on drugs. Some of them were prostituting. Some of them were doing some of the most derogatory things. But when change came in their lives, today some of them are great. They are great teachers. They are great helpers in the community, making a difference in the lives of so many people. And so, my husband and I for 43 years were pastors of the Vernon Park Church of God. We retired about two years ago. We now have a family life community center where young people and seniors can come and interact with each other, where they can feel wanted, loved, and appreciated, and where they have an opportunity to express their God-given talents, and to know their purpose for being here, and to help others. That’s been a great joy which we have shared in the labor movement, in the women’s movement, in the civil rights movement, wherever we go, and I don’t separate them. We don’t, because it’s the total package that God has given us.

Morris: My husband and I are both musicians and we are both inspired by music. You talked about playing the piano at eight years old in the church? Do you recall any of the songs that you used to play?

Wyatt: Oh yes, I recall many of them. When I was very young, we used to sing anthems: “Let Mount Zion Rejoice,” and various wonderful music. As we got older, we would sing more of the hymns and gospel songs. In the last few years, I don’t play as much because I’ve had difficulties with my fingers, but I have many young people who play because we inspired them to do that. We helped them to do it, and in the black church, music was key. It is most important. When you have a ministry combined with the preached word, and it’s a good preached word, and good music, then you are able to help people in a spiritual way that is most outstanding. That’s what we’ve done for the 43 years. We’ve had people come even from abroad different places, to share in our worship because of the reputation for good music and good preaching.

Morris: What kind of musicians do you have in your church?

Wyatt: We have quite a few now. They play the organ; they play the keyboard; they play the saxophone, the drum, and the trumpet.

Morris: What is your favorite gospel music?

Wyatt: There is one that Albertina Walker sings, and here of late she’s been singing that and it is “I’m still here.”

Morris: I think that’s a good note to start to wrap up. I did want to mention that you’ve been married to your husband for

Wyatt: 62 wonderful years!

Morris: It’s been an honor to interview you and be in your home. It’s beautifully decorated for Christmas this year of 2002. What is the hope and the legacy that you hope for the future, for the women’s movement and for the labor movement?

Wyatt: That people will unite together because of our effectiveness. Women and men will unite together and work for peace in the world. Without it, nothing else will really matter. Our role can be different, and there’s a songwriter that said, “Let there be peace on earth, and may it begin with me.”

Morris: Thank you very much, Reverend.

Wyatt: And thank you.

© 2018—Working Women's History Project