Working Womenʼs History Project

Connecting Today with Yesterday

Making Women's History Come Alive

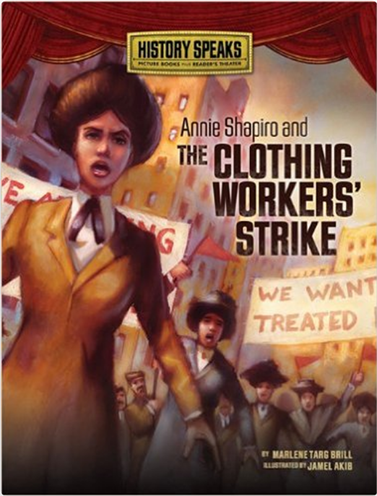

Annie Shapiro and the

Clothing Workers’ Strike

Written by Marlene Targ Brill

Illustrated by Jamel Akib

48pp, History Speaks Picture Books plus Reader’s Theater (Millbrook Press)

(ages 7 to 10)

Reviewed by Amy Laiken

While organizing a Chicago commemoration of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire a few years ago, I researched the early 20th century Chicago garment industry to learn what I could about workers fighting to improve pay and factory conditions here. It was then that I read an old interview with Hannah Shapiro Glick, the heroine of “Annie Shapiro and the Clothing Workers’ Strike,” a children’s book by Marlene Targ Brill. Annie, as she was known to her co-workers at Hart, Schaffner and Marx (HSM), a men’s clothing company, was a 12-year-old Russian Jewish immigrant when she had been forced by her mother’s illness to leave school to go to work to help support her family.

Beautifully illustrated by Jamel Akib, the book follows Annie, starting 5 years later, as she shoulders her sometimes competing responsibilities as a devoted daughter helping with the care and support of younger siblings, and as a worker fighting for economic justice and respect at her workplace. Ms. Targ Brill does a good job of informing young readers about the harsh conditions and arbitrary pay cuts faced by young garment workers in 1910 when the book opens. But she is at her best when she explains how the young Annie begins to inspire others to fight for their rights, while trying to solicit help from the United Garment Workers (initially, unsuccessfully) and later the Women’s Trade Union League, whose financial contributions helped the striking workers.

The story ends on an uplifting note after Mr. Schaffner, although still refusing to recognize a union, did agree to create a committee of workers and management to find ways to resolve workers’ complaints. Annie Shapiro, according to the author’s note, worked at HSM for three more years following the strike. She was a young woman who clearly had leadership skills, and I would like to have read about whether she served on that committee during those three years, and, if so, what role she played. But overall, this book is an excellent way for teachers to present some important Chicago labor history. Ms. Targ Brill, whose sister-in-law was Hannah Shapiro Glick’s niece, includes helpful background information in the author’s note section. The “Performing Reader’s Theater” section, which features a script, makes history come alive for young pupils. Sadly, some of the poor working conditions and anti-worker attitudes that were prevalent a century ago still exist today. Through books like Ms. Targ Brill’s, a younger generation can learn that organizing to fight injustice can indeed make a difference.

© 2018—Working Women's History Project