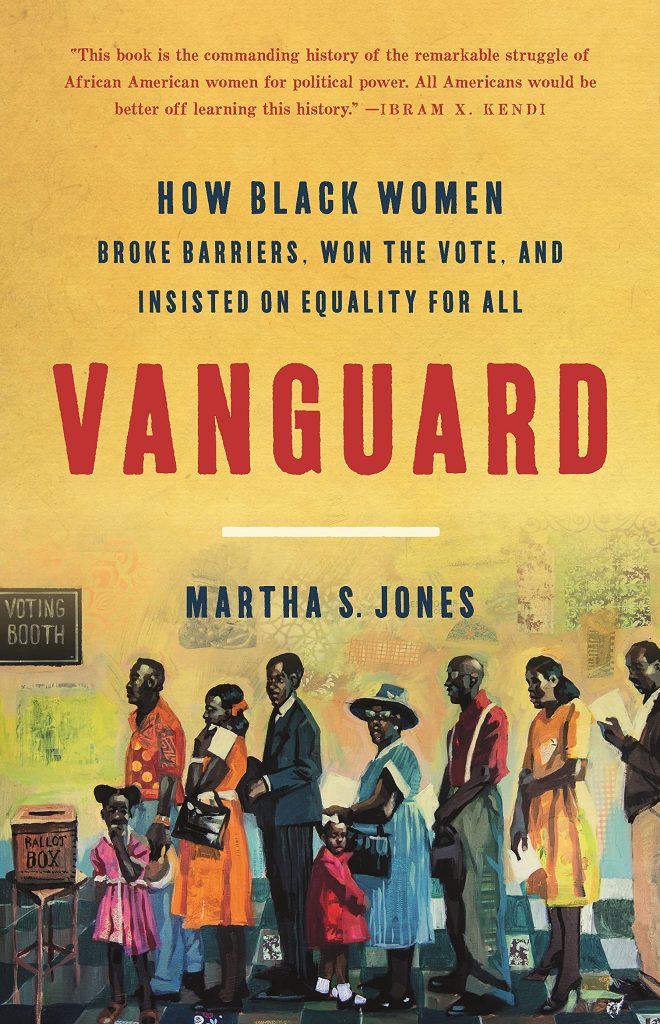

Author: Martha S. Jones

Publication Year: 2020

Publisher: Basic Books

In her new book, Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University and President of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians, Martha S. Jones dives into her family history and the history of the United States through the eyes of Black women.

Starting with her great, great, great grandmother, Nancy Belle Graves, born enslaved in 1808 in Danville, Kentucky, to Susan Davis, Nancy’s oldest daughter, (and the great, great grandmother of Professor Jones), born in 1846 also enslaved, yet had the revolutionary idea that she wanted to vote, Jones paints a picture of women with vision beyond their early station in life.

The ebb and flow of progress and backlash is shown: how the 15th Amendment won the vote for Black men, only to face local laws such as the poll taxes, intimidation, and violence to curtail this right of citizenship. This in turn saw women like Susan Davis form Black women’s clubs.

Then, the book recounts how the passage of the 19th Amendment victory for women’s voting rights opened another door. Susan’s daughter, Fannie, was given an education, as was her husband, and in 1888 she taught first in Covington, Kentucky, then in St. Louis. Fannie spearheaded the construction of the first African American YWCA. She represented her state at the 1936 annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1926 Fannie’s daughter, Susie followed her husband to Greensboro, North Carolina where her father-in-law, father-in-law, Dallas Jones went into politics and rose to become a leader in the local Republican Party during the 1880’s. Then came 1890 and a group of unidentified men urged the election officials to challenge the entire list of Colored (as they were called then) voters on Election Day, not before, ending his political career.

The men and women profiled in the book give us hope for future progress, as well as for the struggle facing backlash against equality. I am reminded of the lessons learned in the labor movement, such as, “each generation has to win it for themselves,” and “solidarity forever” ring true here as well.

This summary leads us to the stories of many from the time the United States broke from England, and the 1773 signing of the Treaty of Paris. In Massachusetts we are informed of the enslaved population challenging their bondage in court cases and winning, leading to laws in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and New York adopting gradual abolition of slavery.

However, in 1816 The American Colonization Society was formed and sent former slaves

to colonies such as Liberia. 1826 saw New York and other states cut out Black men’s access to the polls; states joining the union such as Ohio and Missouri wrote into their constitutions “white men” as a prerequisite to vote.

Voting was not the only platform where people sought rights of leadership. Women found themselves with callings to preach, to teach, to write, and faced not only pushback from white supremacists, but also opposition from Black men who saw women as helpmates not equals. The personal ambitions, conflicts, and distrust among and between other Black women and white women also make up this journey for equality for all.

WWHP recommends Martha S. Jones’ book to anyone who wants a greater understanding of the history of the ways Black women fought for equality.

Within the book are photos and other images from Professor Jones’s personal archives of her relatives to the last picture, which is a photo of Stacey Abrams’ 2018 election watch party.